Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

📱Apple rolls out new parental controls this fall: Just in time for back-to-school season (and kids asking for new iPhones), Apple is rolling out new parental control features with the release of iOS 26 later this year. The updates will give parents more ways to create safer, age-appropriate experiences for kids and teens on Apple devices.

Here’s what’s coming:

These new tools will be free when iOS 26 launches later this year. In the meantime, you can already access Apple’s built-in parental controls — including screen time limits, app approvals, and purchase restrictions — by adding your child to a Family Sharing group. Here’s how to get started.

🤖 APA releases advisory on kids and AI: Artificial intelligence (AI) is popping up everywhere — but how can parents ensure their kids are using it safely? The American Psychological Association (APA) recently released a health advisory on AI and adolescent well-being, with recommendations for parents, tech companies, educators, and policymakers, and more.

Some takeaways for parents include:

The health advisory also includes common-sense recommendations for tech companies that are similar to ongoing conversations about social media safety: kids need better protections from harmful content, and tech companies should take greater steps to create age-appropriate experiences for their youngest users.

For parents, it’s more important than ever to stay involved in what their kids do online, including what apps they use and what they type. If you don’t feel comfortable talking to your kid about AI, that’s understandable — but kids are using it, and it’s shaping their online experiences.

Here’s a place to start: We put together a guide to talking to your kids about the difference between AI friendships and in-person ones. Check it out.

Coming soon: Want to monitor what your child sends on Snapchat, Discord, Roblox, and more? Keep your eyes peeled on the BrightCanary app 👀

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

AI tools can be helpful when used wisely, but they can also blur boundaries and spread misinformation. Whether your child is using ChatGPT to study or exploring AI companions like Replika or Character.ai, it’s important to check in regularly. Here are some conversation starters to help your child think critically, stay safe, and understand the limits of AI.

⏲️ Remember the TikTok ban? President Trump has pushed back the sell-by date again — and he says he has a buyer lined up. The Chinese government would need to approve the sale before it’s official, though.

🛑 The Dutch government recommends that children under 15 stay off TikTok and Instagram, citing psychological and physical problems among kids that use the platforms.

🤨 How can you tell real parenting advice from misinformation on social media? CBS spoke with Emily Oster of Parent Data. Her recommendations include looking for credentials, being mindful if someone is selling an easy solution to a hard problem, and more.

Giving your child their first phone is a big step, and staying connected to their digital world is just as important. That’s why we built BrightCanary: a smarter, safer way to help parents guide, protect, and connect with their child across every app they use.

But how does BrightCanary actually work? In this guide, we’ll cover how to set up BrightCanary and what makes it the best parental monitoring app for iPhone users. Let’s dive in.

BrightCanary uses a secure keyboard on your child’s iPhone or iPad to monitor what they type across apps like:

You can also add your child’s Google account to monitor their activity across Google search and YouTube. If they encounter anything concerning, we’ll let you know.

Unlike other apps, BrightCanary doesn’t require you to guess which apps your child uses. If they type in it, we help you monitor it.

BrightCanary uses a secure iOS keyboard to capture what your child types — no passwords required for most apps. This allows us to monitor content across multiple platforms, while also taking steps to preserve your child’s privacy.

Here’s why parents love BrightCanary:

Did you know? BrightCanary's keyboard never captures passwords or sensitive login data. And unlike other monitoring solutions, you don’t have to plug your child’s phone into your computer or sync with your home WiFi network.

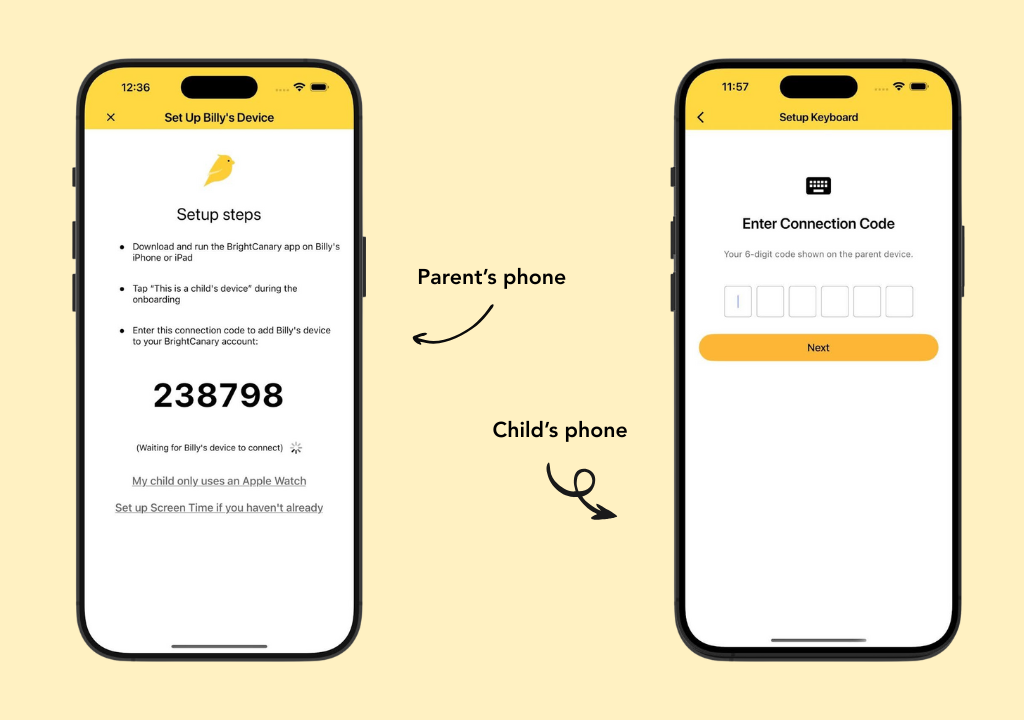

You’ll need your phone and your child’s iPhone or iPad for this one-time setup.

For best results, make BrightCanary the default keyboard and delete all other keyboards (except Emoji). This helps ensure consistent monitoring across all apps.

This feature tracks search history, video views, and concerning content. Here’s how to set it up.

If they already have a Google account:

If you don’t know your child’s logins, here’s how to ask for their passwords.

If you need to set up a Google account:

That’s it! Once you’ve created their Google account, make sure your child uses this information to log into Google and YouTube on their devices. Sometimes, Google's Additional Verification feature prevents BrightCanary from syncing data. Here's how to disable it.

It’s easier to monitor your child’s activity when they have their own Google account. For example, if they use your account to watch YouTube and you sync it with BrightCanary, our app might flag your activity.

If you haven’t already, this is a great opportunity to talk to them about how and why you’re using BrightCanary to keep them safe online. A digital device contract can help lay out rules and expectations for both of you.

You have two options to monitor text messages with BrightCanary. On our Protection plan, you can monitor all the text messages your child sends, and we’ll flag anything concerning in their texts.

If you want more insights, upgrade to Text Message Plus. This plan gives you:

We recommend Text Message Plus for kids who primarily use their Apple Watch to communicate with friends and family.

How to set it up:

You’ll need your device and your child’s device.

That’s it! New text messages may take a few hours to appear at first, and then you’ll start monitoring in real time.

To upgrade, tap Text Message Plus on your dashboard.

We designed the BrightCanary app to give parents detailed insights about their child’s activity. Here are some things you can do, all from your phone.

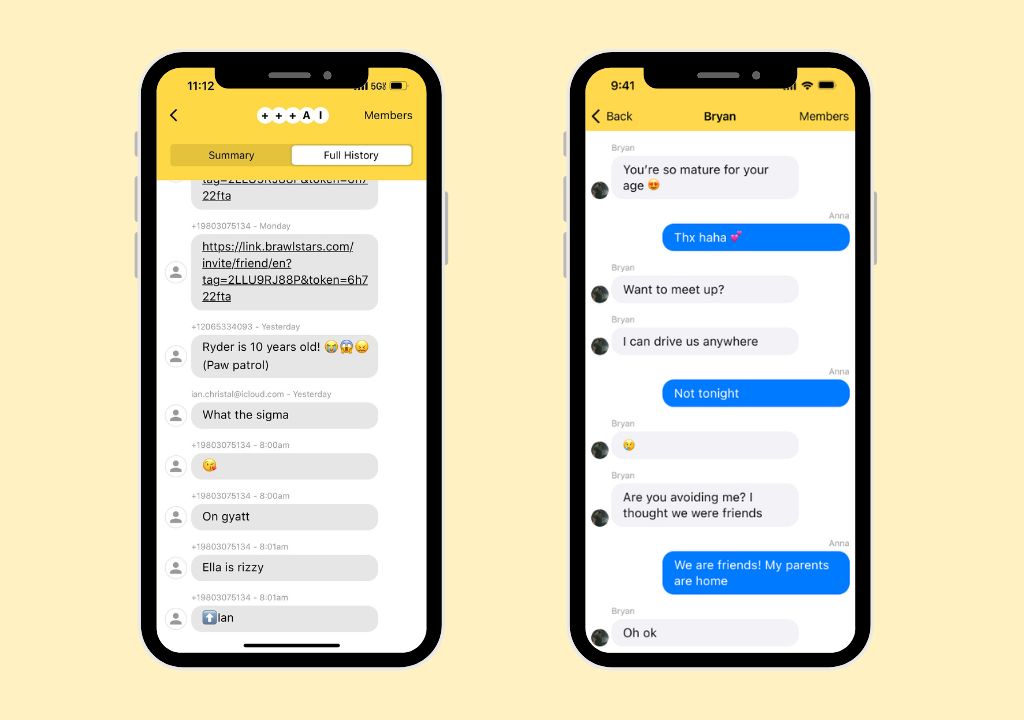

Get an overview of what your child is typing and searching, all in one place. Any concerning content is flagged at the top of the dashboard. You’ll also see recent activity, interests, emotional insights, and topics you might want to discuss with your child.

We use AI to detect red flags, such as suicidal comments, drug content, and explicit messages. You’ll be able to view anything we detect and the app on which it occurred.

View a transcript of your child’s latest keystrokes and the app they used.

Whether your child is talking about a new TV series or using slang they picked up online, you’ll get a summary of their interests and pop culture chats in this section.

Get detailed summaries of your child’s emotional state based on their activity. You can even tap the quotes to see more context.

Not sure how to bring something up? Our built-in AI parenting coach gives you instant, age-appropriate advice on tricky topics like sexting, bullying, and more.

Monitoring should be a partnership, not a punishment. Here’s how to introduce BrightCanary to your child:

You can also use our free Digital Device Contract to help set expectations together

Ready to try BrightCanary? Download BrightCanary from the App Store and start your free trial today. Setup takes just a few minutes — and you’ll gain real peace of mind for years to come.

Unlike other parental monitoring apps, BrightCanary was designed for iOS devices. That means we show features that other apps don’t, like full text message conversations and the messages your child sends on apps like Snapchat and Discord. Here’s how BrightCanary compares on Apple devices.

You need your child’s device during setup, but unlike other child safety apps, we don’t slow down your child’s phone performance. However, we recommend that parents use BrightCanary in collaboration with their kids.

Explain why you’re using BrightCanary, how you’ll use it, and why it’s important to help keep them safe. Some of our parents make BrightCanary monitoring a requirement if a child wants their own phone and add it to their family’s digital device contract.

Yup. We’re real people with families behind this app! BrightCanary was founded in 2022. Based in Seattle, we’re a small team of parents who want to help parents guide, protect, and connect with their kids as they learn how to navigate the digital world. Learn more about our story.

Check out more questions at our FAQ.

Parenting in the digital age can feel like an uphill battle. Fortunately, parental monitoring apps like BrightCanary are tools you can add to your parenting toolbox. And a growing number of experts recommend monitoring your child’s online accounts, from the American Psychological Association to the U.S. Surgeon General.

Remember, parental monitoring is just one piece of the puzzle — it’s just as important to have regular conversations with your child about their online activity and how to handle what they see online.

Download the BrightCanary app from the App Store today and start your free trial!

For more parenting tips, here’s how to help your child use social media responsibly. Subscribe to our newsletter for parenting news, advice, and resources twice a month.

Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

😕 9 in 10 teens have been cyberbullied, study says: If your child is online, there’s a good chance they’ve dealt with harassment. Cyberbullying is defined as willful and repeated harm inflicted through electronic devices, typically through social media, gaming platforms, or chat environments. Researchers surveyed nearly 2,700 middle and high school students in the U.S. and found that cyberbullying is widespread among adolescents, and it can lead to serious psychological harm.

The most common forms of cyberbullying reported by adolescents were:

The study found that cyberbullying of any type (no matter how subtle) could contribute to trauma symptoms, such as PTSD, anxiety, and emotional distress. “What mattered most was the overall amount of cyberbullying: the more often a student was targeted, the more trauma symptoms they showed,” lead researcher Sameer Hinduja said in a news release.

Kids might struggle to talk about cyberbullying because they fear social repercussions, like getting in trouble with their friend group or having their device taken away. If you haven’t already, talk to your child about what to do if someone makes them uncomfortable online and how to deal with a bully. For more tips, check out our guides on how to deal with cyberbullying through texting and what to do if you find out your child is the bully.

🤦 Instagram Teen Accounts still show sensitive content: Meta’s Teen Accounts are meant to give added protections to teen users, including limiting the ability for strangers to contact them and filter out sensitive content. But users report receiving recommended content that promoted eating disorders, explicit acts, and hate content, despite using Teen Accounts.

“The danger they face isn’t just bad people on the internet — it’s also the app’s recommendation algorithm, which decides what your kids see and demonstrates the frightening habit of taking them in dark directions,” writes Geoffrey A. Fowler of The Washington Post.

This is just another frustrating reminder that social media companies’ solutions aren’t foolproof and can fail in the places they’re meant to protect kids. This is also why a growing number of experts advocate for more parental oversight on their kids’ devices and regular online safety discussions. It’s still a good idea to set parental controls, but monitoring doesn’t stop there — it’s an ongoing series of conversations and check-ins.

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

Not all screen time is created equal. While it’s easy for kids to fall into endless scrolling mode, screens can also be tools for connection, creativity, and fun. Here are five conversation-starters to help your tween or teen think about healthier, more intentional ways to use their devices this summer:

🍿 Need ideas for family movie night? Check out this list of new kids shows and movies coming to Netflix this month.

📵 “Teachers don’t have to fight an impossible battle against tech. Students talk to each other between classes. The cafeteria has the sound of conversation. Teachers cover material faster. Cyberbullying has fallen.” Gilbert Schuerch, a veteran high school teacher in Harlem, NYC, shares what happened at his school after they banned phones for a year.

🤯 Did you know that teens use an average of 40 apps per week? That’s a lot to keep up with. We’re working on an easier way to stay informed — stay tuned for news from BrightCanary.

Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

😵💫 Is social media distracting you from connecting with your child? A new study found that excessive social media use makes it more difficult to build a meaningful relationship with your child. Studies have shown that social media can actually benefit parent-child interaction, like watching educational videos or helping parents learn more about their children’s interests … but there’s a limit. Excessive social media use can weaken both the frequency and quality of face-to-face communication. Plus, there’s a significant correlation between overall family stress and social media addiction, which means kids dealing with family conflict and pressure are more likely to relieve their emotions by using social media — which reduces communication and interaction with their parents. Talk about a vicious cycle.

These findings come on the heels of a separate study that found parents’ use of technology in their child’s presence led to negative behaviors in kids under 5, including poorer cognition and social behavior, lower attachment, and higher levels of screen time. Big yikes. The author doesn’t define “excessive social media use,” but we define it as any level of social media use that interferes with your ability to be present with your child (a phenomenon also known as “technoference”). If you’re struggling with your own screen time, here are our tips on how parents can be great digital role models for their kids.

🚫 A majority of kids aren’t reporting online harassment: Seventy-one percent of kids say they’ve experienced harm online, but only 36% say they’ve reported it, according to new findings from Internet Matters. Blocking and reporting tools are meant to help people protect their online experiences by limiting interactions with bullies and flagging inappropriate content for removal, and they’re widely available on platforms like Roblox, TikTok, and Instagram. So, why aren’t kids using them? The report highlighted the following roadblocks in the reporting process: unclear language, confusing processes, concerns about anonymity, and lack of clarity about what happens after a report is submitted.

Blocking and reporting tools are only as good as our ability to use them, and that goes double for kids. While there are steps platforms can take to make their reporting tools better (like making the process clearer and prioritizing reports from kids), parents can play a role, too. Have a conversation with your child about how reporting tools work and when to use them, and make it clear that you’re in this together — your child doesn’t have to navigate problematic comments on their own.

🚨 Kids are destroying Chromebooks for TikTok clout: Kids are letting out some steam at the end of the school year … by vandalizing school-issued Chromebooks. The latest TikTok challenge has students purposefully sticking things in the USB ports, like pencils or pushpins, to short-circuit the system. Some Chromebooks issue a small cloud of smoke. Others ignite. At least one middle schooler is being referred to juvenile court to face charges. Like other viral challenges, TikTok is getting the blame for popularizing the so-called “Chromebook Challenge” — but the reality is that any social platform, like YouTube Shorts or Instagram Reels, can expose your child to ridiculous-bordering-on-dangerous trends. On the BrightCanary blog, we’re sharing some tips for how to talk to your child about TikTok challenges and the consequences of their actions.

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

It’s 10 p.m. Do you know where your children are? If they’re in their bedroom watching fan theories about the next Marvel movie on YouTube, this is your sign to set summer screen time limits. At the end of the school year, your kid might be tempted to use their devices 24/7. Here are some ways to talk about screen time limits, why they’re a good idea, and how to set them.

✔️ President Trump has signed the Take It Down Act into law, which would criminalize sharing intimate images without consent.

📵 “Until you’re an adult and able to recognise the many ways in which people act deviantly to advance their own interests, you should not be online. The minute there is instant messaging I think it gets dangerous.” The Guardian spoke with digital natives about access to technology and why parents should rethink giving their kids unrestricted access to the internet and social media.

🙅 Former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy recommends delaying social media access for as long as possible. He cited 16 years old as a benchmark, but the exact age varies from child to child.

If your child loves Roblox, you’re not alone. With over 70 million daily users and approximately 40 million games, it’s one of the most popular online platforms, period. But Roblox’s open-world structure and chat features can leave you wondering, “How can I monitor what my child is doing on Roblox … without hovering?”

The good news is that there are smart, effective ways to supervise your child’s Roblox activity. This article walks you through how to monitor Roblox, what to watch for, and how to use tools like BrightCanary to get insights into your child’s activity.

Roblox can be a space for entertainment and creativity — but like any online platform, it can also expose kids to:

Monitoring isn’t just about safety. It’s a way to support your child’s digital well-being. While Roblox parental controls allow parents to adjust content and chat settings (which we’ll discuss later), it doesn’t give parents full visibility into what their child actually does on the platform.

When you monitor an online video game platform, you want to stay aware of your child’s chat activity and messages, in-game interactions, time spent on the app, and their mood and behavior.

Let’s cover a few ways you can use available tools to stay on top of your child’s activity.

You can view basic usage data directly in Roblox:

There are a few limitations with this approach, though. If your child is super active on Roblox, it’s easier to miss something, like a concerning message buried in their chat history. Plus, manually reviewing their activity is time-consuming.

If you take this route, we don’t recommend doing it behind your child’s back. Explain why you want to check their account and what you’re concerned about.

A parent account allows you to approve certain actions for your child on Roblox. You’ll be able to set parental controls, including chat controls and spending limits, and view your child’s Roblox usage and on-platform friends.

Additionally, you can create an avatar to play with your child — which is a great way to familiarize yourself with the platform.

One limitation of Roblox’s parental controls is that you won’t be able to monitor what your child messages to their friends. For that, you’ll either need to spot-check their chats or use a monitoring app.

Psst: BrightCanary monitors what your child types across all the apps they use, including Roblox chats on their iPhone or iPad. Download on the App Store today and start your free trial.

Roblox allows you to set screen time limits on how much time your child can play — you can access this setting under Parental Controls once you set up a parent account.

You can also use Apple Screen Time or Google Family Link to:

This step helps manage playtime and reduce the risk of excessive screen use. We recommend setting screen time limits about an hour before bedtime to encourage your child to wind down.

Let’s say your child is playing Rainbox Friends on Roblox, and you’re worried about the game’s horror elements. If you see something concerning — like mature game content, new contacts you don’t recognize, or changes in your child’s mood — here’s how to respond:

Parental controls are a great starting point, but they only go so far. Staying involved with your child’s online activity — including what they play and what platforms they frequent — helps you support your child’s safety, social development, and digital literacy.

BrightCanary can help. Our app monitors what your child types across your child’s favorite apps, including Roblox, YouTube, Google, and even texts. You’ll get summaries, alerts, and insights so you can stay informed — without reading every message. Download BrightCanary and start your free trial today.

Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

🚫 Don’t let teens make friends with AI chatbots, experts say: The AI characters on platforms like Character.ai and Replika call themselves virtual friends — but they’re more dangerous than they seem, particularly for young people. That’s according to a new risk assessment recently released by Common Sense Media, which concludes that all AI social platforms should be off-limits for anyone under 18. Some of the risks include easily bypassed safety features, harmful advice, and readily available sexual interactions despite speaking with underage users.

"Our testing showed these systems easily produce harmful responses including sexual misconduct, stereotypes, and dangerous 'advice' that, if followed, could have life-threatening or deadly real-world impact for teens and other vulnerable people,” said James P. Steyer, founder and CEO of Common Sense Media.

Learn more about the rise and risks of social AI platforms and why teens use them.

🏛️ The Kids Online Safety Act is back: Guess who’s back, back again? Sorry, Eminem — we’re talking about KOSA. The child safety bill aims to boost online privacy and safety for children, creating sweeping regulations that reduce the addictive nature and mental health impact of social media platforms. As a recap, it sailed through the Senate last year but failed to pass the House of Representatives. The new bill, reintroduced by Sens. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), contains the same text approved by the Senate, with several changes to “make clear that KOSA would not censor, limit, or remove any content from the internet.” KOSA has received bipartisan support, including endorsements from Apple and X, but has faced criticism from other organizations due to free speech concerns. It’s not clear yet if the House will put the bill to a vote, but we’ll keep you posted.

📱 Teens with mental health conditions spend more time on social media: Why do we talk so often about the risks of unrestricted social media access? Because emerging research shows that it’s hurting our kids. Young people with mental health conditions like anxiety or depression are more likely to compare themselves to others on social media, struggle with self-control, and experience mood changes tied to likes and comments, according to a new study led by University of Cambridge researchers. On average, teens with any mental health condition spent about 50 minutes more daily on social media than those without. Correlation doesn’t equal causation, but these findings suggest that social media may amplify emotional challenges among teens — all the more reason to have a discussion not only about what social platforms your child uses, but also how often they use them and what content they consume. Keep reading about the relationship between social media and teen mental health, or dig into how social media impacts teen anxiety.

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

We’re rapidly approaching finals season. Is your teen more stressed than normal? Here are some tips on how to talk to them about managing and navigating academic stress.

📵 It’s time to keep phones out of classrooms, argues Pinterest CEO Bill Ready. “Rather than focusing solely on increasing view time through addictive features, we must help young people be more intentional with how they spend their time online.”

☁️ In the age of smartphones, parents and their kids are losing the ability to daydream — and losing the positive effects of a wandering mind, including self-awareness, creativity, and reflective compassion. Here’s how to fight it. Spoiler: Try being bored more often.

🤝 Share this newsletter to a friend and help them be the most informed parent in the room. Subscribe here.

Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

📉 Teens say social media is hurting their mental health, and many are cutting back: According to a new Pew Research Center report, nearly half of U.S. teens say social media has a mostly negative effect on people their age. That’s a significant jump from 2022, when just 32% said the same. Nearly half of teens (45%) say they spend too much time scrolling their feeds, and 44% say they’ve tried to cut back. Some other sobering stats that will make you want to delete Instagram and Snap:

One teen summed it up: "People seem to let themselves be affected by the opinions of people they don’t know, and it wreaks havoc upon people’s states of mind."

More teens are starting to recognize the toll social media can take — and many are already trying to build better digital habits. Parents can help by modeling those habits, encouraging breaks, and keeping lines of communication open. Talk to your teen about what they’re seeing, who they’re following, and how they feel after being online. Their answers might surprise you.

🤖 Instagram will use AI to catch kids lying about their age: Meta, Instagram’s parent company, announced that it will use artificial intelligence to proactively detect users who have lied about their age when signing up. Instagram has restricted settings for teen users, but it’s relatively easy for kids to bypass age verification. This new feature will look at the type of content a user interacts with, their profile information, and when the account was created to determine if they’re underage. Meta says the goal is to make Instagram safer for younger users, but it also comes at a time when more states are pushing for stronger age verification laws and fed-up parents protest outside of the headquarters of major social media companies.

AI can help flag accounts, but it’s not foolproof. This is a good time to double-check that your child has the right birthdate listed in their account, that they’re using a Teen Account, and that you’ve reviewed their privacy settings. Learn more about how Instagram compares to Snapchat and TikTok in terms of safety settings.

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

From social media apps to search history, kids and teens are navigating a digital world that collects more data than they may realize. But not all of it is used in ways they understand or would agree to. Here are a few conversation-starters to help you talk with your child about online privacy.

💸 How young is too young to have a credit card? This essay on Salon explores consumerism among Gen Alpha and the problem with learning how to spend before learning how to save.

🫥 Online interactions will never beat the experience of face-to-face conversations — but when kids grow up mostly with screens, they miss out on interactions that matter, per this essay on After Babel. “The bottom line is that every in-person conversation that is replaced or disrupted by a device is a missed opportunity for kids to feel more connected, loved, and alive in the short term; to foster meaningful relationships over time; and to become even passable communicators by the time they reach adulthood.”

⚖️ Texas lawmakers have advanced bills that would ban kids under age 16 from using social media and would require social media platforms to add warning labels. The bills head to the state’s Senate next.

Keeping your kids safe in the digital world means staying informed — especially about who they’re texting. But if your child uses an iPhone, Apple’s strict privacy settings can make it tough to monitor text messages. Most monitoring apps are built for Android and offer limited features for iOS users (even though an overwhelming majority of teens use iPhones).

This guide breaks down the best apps for monitoring text messages on iPhone, highlighting their features, pros, and cons to help parents make the right choice. Let’s dive in.

Teens receive hundreds of notifications per day, and not all of those messages are positive. Kids can experience cyberbullying, inappropriate content, and peer pressure, among other red flags. And for many teens, texts are the main way they communicate — often without adults seeing what’s going on.

Having regular conversations about online safety and device use is an important part of keeping kids safe on their devices. But for parents who also want to check their child’s texts, they’re faced with a challenge: they can attempt to manually review hundreds of texts per day, or sit back and hope for the best. Yikes.

Apple’s free parental controls give parents a way to limit who can text their children, but they can’t easily review what their texts say. Text message monitoring apps bridge that gap, giving parents the insights they need while supporting their kids’ growing independence.

You’re busy. Here’s a comparison table to help you quickly evaluate the top-rated contenders:

| Feature | BrightCanary | Bark | MMGuardian |

| View full text threads | Yes | No | Yes |

| Detect deleted messages | Yes | Partial | Yes |

| AI-powered summaries | Yes | Yes | No |

| Emotional insights + conversation tips | Yes | No | No |

| Price | Free with paid plans available | $99/year | $69.99/year |

| Monitor away from home | Yes | Must be connected to home WiFi | Must be connected to home WiFi |

BrightCanary is the only child safety app that comprehensively monitors iPhone text messages, even when they’re out of the house. The app gives parents the ability to read full text threads, learn about their children’s emotional well-being, view AI summaries, and even get coaching prompts to have better parent-child conversations.

Pros:

Cons:

Final takeaway: Best for parents looking for comprehensive text message monitoring on iPhones with AI-powered support.

Bark is one of the most popular apps for monitoring online activity. However, Bark text monitoring is limited for iOS. Parents can either monitor text messages by installing an app on their desktop or a separate device called Bark Home. The app only scans the child’s text messages while they’re at home.

Pros:

Cons:

Final takeaway: Bark is best for parents who want to monitor texts on Android devices and have access to other monitoring features, like screen time limits and website blocking.

MMGuardian offers specific parental controls for iPhones, but like Bark, you’ll need to install a separate app and can only scan your child’s texts when they’re on the same WiFi. However, for parents who want more detailed insights, MMGuardian does show full text threads.

Pros:

Cons:

Final takeaway: MMGuardian is useful for parents who are okay with text message monitoring that requires syncing devices at home. It also has screen time limits available within the app, although these features are also freely available with Apple Screen Time.

Some companies have created their own phones that limit app usage, monitor messages, and have GPS tracking.

These phones treat text messages differently: Gabb offers its own messaging app called Gabb Messenger, while Pinwheel and Troomi use an Android SMS app that parents can monitor.

Bark doesn’t allow kids to delete texts without the parent’s permission, and the phone uses Bark’s software to identify inappropriate content.

Pros:

Cons:

Final takeaway: Best for parents of younger kids who need basic, controlled phone access, but less useful for older teens.

Apple makes it difficult for most third-party apps to monitor text messages. That’s why so many options out there are limited, or they have more features available for Android phones.

If you don’t want to install any extra software or rely on your desktop to check on your child’s messages, that narrows your options. For example, Bark and MMGuardian can only scan your child’s texts when they’re home. In comparison, BrightCanary can monitor your child’s texts even when they’re at school or with a friend.

Many child safety apps offer text monitoring alongside other parental controls, such as location tracking, social media monitoring, and the ability to restrict who can contact your child. If you want your text monitoring app to do more, that’s another thing to consider. (These features are also freely available with Apple Screen Time and Find My.)

Finally, pricing is another important factor. Most child safety apps operate on a subscription basis. Are you getting the most bang for your buck? If you run into an issue or have feedback, is there a US-based support team available?

When it comes to iPhone text monitoring, BrightCanary offers the most comprehensive support: full message access, deleted message recovery, AI-generated summaries, and emotional insights.

In today’s digital landscape, it’s essential to stay involved with your child’s online life. The best apps for monitoring text messages on iPhone give you the insights you need, all in a way that fits into your daily routine. Staying informed doesn’t have to be a chore or feel overwhelming. It’s a key part of guiding, protecting, and supporting your child today.

Yes. Child safety apps like BrightCanary and MMGuardian allow you to monitor deleted text messages.

Maintain open communication with your child. Explain that you trust them, but texting can expose them to serious risks. Text monitoring can give your child more independence, with a safety net. Let your child know that your goal isn’t to spy on them. Many BrightCanary parents only choose to read text summaries, and they’ll only read full threads if something looks concerning.

It depends on the app. BrightCanary monitors group chats and even provides insights into the emotional content of those conversations.

BrightCanary stands out for its iPhone-specific capabilities, offering the most comprehensive text monitoring features, including deleted messages and AI insights.

BrightCanary has a free plan and subscription options. See how BrightCanary’s pricing compares to other text monitoring apps.

Download BrightCanary on your device, then create an account for your child. Add their iCloud login information. BrightCanary will sync with their Apple account and begin monitoring their messages. Learn more about how to set up BrightCanary text message monitoring.

Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

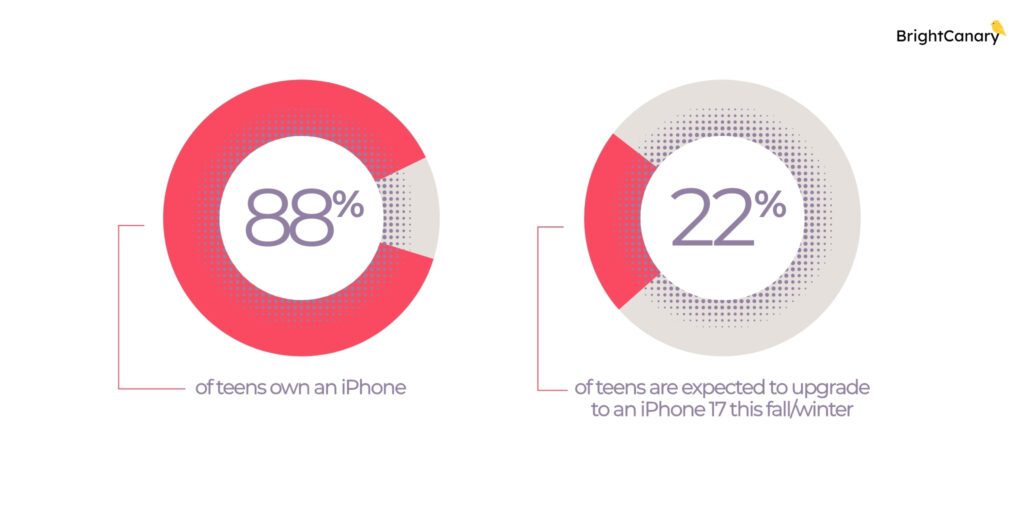

📱Majority of teens use iPhones, Instagram, and Netflix: Android users are feeling lonely these days. An overwhelming majority (88%) of teens own an iPhone, and 25% of teens are expected to upgrade to an iPhone 17 later this year. That data comes from the latest Piper Sandler survey of more than 6,000 teens (average age: 16.2 years). Other highlights from the survey:

Our take: If your teen doesn’t have an iPhone, expect pressure from their friends about it. Now’s a good time to talk about how to navigate peer pressure together, and if you do decide to give them an iPhone, make sure you take time to set up free Apple parental controls.

🪣 Why do kids fall for social media trends? If you’ve seen your feed flooded with AI-generated Studio Ghibli-style images lately, you're witnessing the latest viral social media trend. But why do these trends spread so fast—and how might they influence your teen? A recent Psychology Today article breaks it down:

Herd mentality: Teens are hardwired to seek belonging. When everyone is jumping on a trend, it feels natural, and even necessary, to join in. Not participating feels like being left out of an inside joke.

Identity exploration: Trends offer a low-stakes way for teens to try on different versions of themselves and signal who they are (or who they want to be).

Dopamine boost: Every like, share, and positive comment triggers the brain’s reward system, making social media feel even more addictive.

Not all trends are harmless. Risky challenges like the "Blackout Challenge" or the "Tide Pod Challenge" exploit the same psychological wiring: peer pressure, the search for approval, and the need to fit in. Teens may engage in risky behavior without fully understanding the consequences.

Talk to your teen about why trends are so tempting — and why not every trend is worth following. Remind them that it’s okay to sit out a trend, even if everyone else seems to be doing it.

🥱 Social media before bedtime is wrecking your child’s sleep quality: Here’s yet another reason to keep phones out of the bedroom. A new study found that late-night social media use — specifically, scrolling through emotionally charged (doomscrolling, political posts) and comparing oneself to others — is linked to poor sleep quality. As one of the study’s co-authors, Brian Chin, writes on The Conversation, “In other words, that late-night scroll isn’t harmless − it’s quietly rewiring your sleep and well-being.”

The study focused on people between the ages of 18–30, but the findings are even more alarming when we think about our kids and their developing brains. We recommend keeping phones out of the bedroom and winding down an hour before bed. Bonus points if you do this as a family — here are 11 of our favorite screen-free activities to help everyone unplug and relax before lights out.

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

Let’s talk about peer pressure. Whether it’s a friend pushing your teen to upgrade their phone (sorry, green bubble crew) or encouraging them to do something that feels wrong, it’s important to help your teen recognize peer pressure and know when to step back — or ask an adult for help. Here are a few ways to start the conversation.

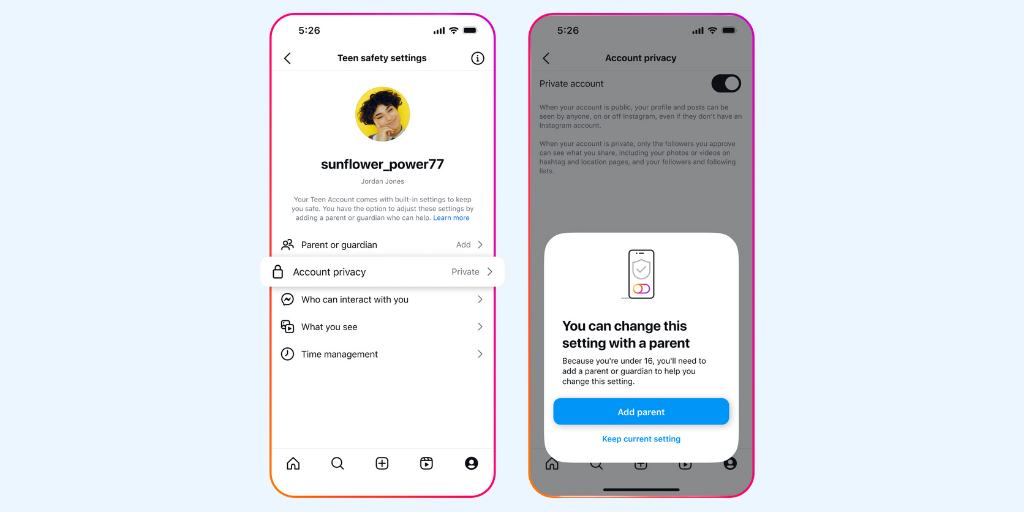

🔒 Meta recently announced more teen safety features across its platforms: teens can no longer use Instagram Live unless a parent or guardian enables the feature, and any potentially explicit images in direct messages will automatically be blurred for users under 16. (Seems like those should have been implemented years ago, but hey, better late than never.) Instagram’s Teen Accounts, which feature built-in privacy and content controls, are also rolling out to Facebook and Messenger.

🚬 Are Google, X, and Facebook modern-day tobacco companies? Check out this opinion article in Scientific American and let us know what you think.

🎮 Is your child on Roblox? Take a closer look at their privacy settings and who they interact with on the platform. The Guardian reports that Roblox is exposing children to grooming, pornography, violent content, and abusive speech. Here’s our guide to Roblox parental controls.

Welcome to Parent Pixels, a parenting newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. This week:

🙅 Smartphones can be good for kids … if they avoid social media: Initial data from a survey of more than 1,500 children suggests that smartphones can be beneficial to mental health and social well-being — unless Timmy starts using TikTok or any other social media. Researchers surveyed children ages 11–13 and found that:

The findings align with results from a separate study, which found that social media use is associated with a rise in loneliness, and feeling lonely can also lead to more social media use over time — creating a feedback loop that’s hard to break.

Our take: More parents are talking about delaying giving kids access to social media. But it’s important to remember that smartphones themselves can be risky, too, due to risks like texts from strangers and cyberbullies. Use those parental controls, monitor your child’s texts, and teach your child how to use their devices responsibly.

⚠️ FOMO makes young adults more susceptible to online scams: Two recent studies of Instagram users between the ages of 16–29 show that kids don’t want to miss out on a social experience, even if they end up falling for a phishing scam. Researchers found that 82.9% fell for a suspicious link in a message at least once, and particularly for those that appeared to be from a friend or a follower with a message like “Check out this private event happening tonight!” The reason: Fear of Missing Out, or FOMO — the fear of not being included in something fun with their peers.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, the lead author of both studies, Jennifer Klütsch, shared the following advice to protect young adults from phishing scams:

🤳 Most parents admit their kids need a digital detox: According to research from the Modern Family Index, a majority of parents (73%) say their kids could need to take a break from screens and devices. Broken down by age:

A “digital detox” is a set period where a person intentionally avoids digital devices, such as smartphones or tablets, with the goal of breaking problematic behaviors and learning balance. Interested in trying out a digital detox for your child? Here are our tips on how to take a screen break successfully. (Psst: It’s even better when you do it as a family.)

Parent Pixels is a biweekly newsletter filled with practical advice, news, and resources to support you and your kids in the digital age. Want this newsletter delivered to your inbox a day early? Subscribe here.

Online scams can happen to anyone, but scammers are getting more creative — and they’re increasingly targeting kids. Parents, talk to your kids about online safety and how to stop a scammer in their tracks. Here’s how to approach the conversation.

🤷 TikTok lives again — for another 75 days, at least. President Trump has extended the deadline for ByteDance to sell its social media platform to an American buyer. Interested purchasers include Amazon, MrBeast, and Perplexity AI.

📲 Utah recently became the first state to pass a law that requires app stores to verify users’ ages and receive parental consent for minors to download applications.

🫥 “Our kids are the least flourishing generation we know of.” We’re sitting with this conversation between Ezra Klein and Jonathan Haidt, social psychologist and author of The Anxious Generation.